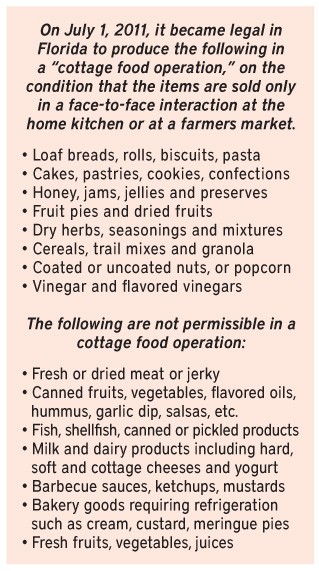

At the Dandelion Communitea Café, a homey vegetarian hangout just outside of downtown, it’s rare to hear people chatting excitedly about Republican policy initiatives. But on Oct. 20, about two dozen people crowded into the café’s largest room to hear, somewhat belatedly, about the good news from Republicans in Tallahassee: Effective July 1, it became legal to own and operate a “cottage food operation” in the state of Florida without the need for a preliminary government inspection by state food authorities. Florida law defines cottage food operations as small businesses that sell “low risk” homemade foods – chiefly, breads and other baked goods – and as long as they meet certain conditions and bring in less than $15,000 per year in profit, the change in the law makes it easier for them to bring their goods to the marketplace.

Though critics insist that the change in the law presents a potential safety risk and conflicts with county and municipal laws, Rep. Steve Crisafulli, R-Merritt Island, the sponsor of the initiative, says the economic benefits outweigh health risks. “The purpose of the legislation is to allow Floridians to test the waters for a small, home-based business of their own,” Crisafulli wrote in an email about the law.

Before the enactment of this year’s cottage foods legislation, those who wished to sell baked goods out of a home or at a farmer’s market needed to acquire, at the very least, an annual food permit from the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. The going rate of an FDACS “confectionary limited sales” permit is only $130, but that figure is somewhat deceptive: The state will only grant such a permit after ensuring that the product is made in a kitchen meeting specifications found rarely, if ever, in the average home. Therefore, many Florida bakers who sell their goods have traditionally been required to rent space at commissary kitchens, which charge anywhere from $10 to $25 per hour, or between $150 and $300 per month. What’s more, some commissaries, such as Chateau Kitchen in Winter Park, will only accept chefs who have already purchased liability insurance. In other words, the path toward a career as an independent baker could be better described as a high-stakes Hail Mary pass rather than a modest series of stepping stones. “This [new law] has cut 75 percent out of the cost of getting operational,” says Gabriela Othon Lothrop, director of the Audubon Park Farmers Market. “With this law, the liability is on the consumer.”

To the commissary kitchens themselves, this development would appear to foretell a decline in business, but Bob Jones, owner of A1 Commissaries in the Pine Castle area, said he’s only lost one customer due to the law change, which he derisively calls the “cottage cheese act.” He predicts that the law will be overturned within “six to eight months, maybe a year,” due to news of consumers sickened by bad food.

“I would say its Russian Roulette,” Jones says. “And eventually, you’re going to lose.” He rattled off a list of the dangers that a cottage operation could pose – such as the use of wooden cutting boards, outlawed in licensed Florida kitchens because they can harbor bacteria – and suggested that the exacting kitchen specifications spelled out by the state exist for good reason. “We have much more of a controlled environment [in a licensed kitchen], whereas at home, there is no controlled environment,” Jones says.

Somewhere in the middle of the spectrum of enthusiasm for the new cottage law are the smaller regulatory forces – the counties, cities and farmers markets themselves – which, at least in Central Florida, don’t appear to be anywhere near in harmony with the state. The Winter Park City Commission, for instance, decided on Aug. 22 that it would still require food vendors at its farmers market to be licensed by the state. In addition, it’s still illegal in Orange County to sell food out of your home, though county officials could not give the Orlando Weekly a clear answer as to whether the laws would be changed to accommodate cottage operations. “Are we then turning all these residential units into commercial-type ventures where people can come and go as they please?” Tim Boldig, the county zoning chief, wondered aloud. “We’ve got to figure that out.”

The city of Orlando is also uncertain what it will do – it has not yet added the “cottage food operations” category to its home occupation application form, and spokeswoman Cassandra Lafser says the city is still “conducting research into this area as it is a newer classification.”

Given the enduring confusion over which cottage operations are legal everywhere – and the somewhat unnerving possibility that the state reserves the right to inspect your home kitchen after receiving a consumer complaint – some local confectionary entrepreneurs, like Kelly Burroughs of Ruby’s Sweetery, are opting to shell out the money for licensing anyway. “I think it’s just peace of mind for me,” she says. “Knowing that I’m protected.”